Walking down Madison Avenue on a sunny afternoon last week Steve Martin had the look of a movie star in thin disguise, wearing tinted glasses and a charcoal fedora that covered his familiar white head of hair.

But once inside the Gagosian Gallery, one of the most high-powered galleries in New York, he peeled off his coat, revealing a dark suit, burgundy tie and perfectly polished black shoes that made him look more like one of the art dealers he describes in his new novel.

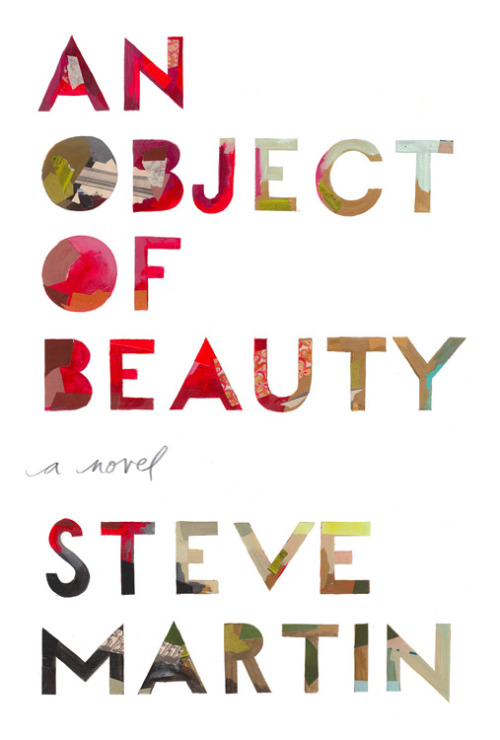

Mr. Martin was there to discuss the book, “An Object of Beauty,” a tale set in the Manhattan art world that draws from decades of personal observation. He is a longtime private collector. His friends include mega dealers like Larry Gagosian and William Acquavella, whose galleries — separated by a few blocks in an art-rich pocket of the Upper East Side — make regular appearances in the novel.

But Mr. Martin insisted repeatedly that he is far from an authority on the subject, and he often seemed more comfortable talking about art books than artworks.

“I’m not an expert,” he said, in his trademark dry sincerity. “Trust me, they don’t need me.”

At the Gagosian, Mr. Martin bypassed a room full of John Currin paintings in luscious shades of red, cream and gold, heading first for a long, narrow hallway where hundreds of books and catalogs were on display.

“Someone said to me, these libraries aren’t important anymore, because you can get it all online,” he said, gazing at the floor-to-ceiling bookshelves. “But you can’t. If you Google an artist and Google the images, you get no information — you don’t get where the painting is, you don’t get the medium, you don’t get the sizes, you don’t get the provenance. So these libraries are really important.”

Mr. Martin, 65, has distanced himself from his days as a wacky stand-up comedian but remains a comic actor who is also a regularly touring banjo player, children’s book author, essayist and novelist. Next year he will appear in a film about competitive bird-watching, “The Big Year,” and release a banjo record, “Rare Bird Alert.”

In person he is quiet, serious and polite, holding open doors and pressing elevator buttons — not the gangly goofball of his longtime public persona. And at times he is a little self-conscious. Rounding the corner of Madison Avenue and 79th Street, he noticed a photographer and grimaced. “I hate that my picture’s being taken in my fat coat,” he said, tugging at the hem of his boxy gray Zegna jacket.

Mr. Martin first became engrossed in art while in college, learning the basics from a close artist friend and a dealer with a large library. Traveling around the country doing his comedy show, he stopped in museums, usually in college towns, picking up books along the way.

“I have a theory that some people are born to it, and some people acquire it,” he said. “And I acquired it.”

The first significant piece he collected was a print by Ed Ruscha that he got rid of decades ago. “It’s a long story,” he said. “I sold it when I angrily left L.A.” (It is possible he needed to lose the print to forget Los Angeles, considering how closely Mr. Ruscha’s work mirrors the city.)

His current collection defies characterization, he said, allowing only that he had a mix of 19th- and 20th-century American art and “a French impressionist picture.” Not long ago he bought a painting by William Michael Harnett, a 19th-century still-life painter.

“It’s absolutely great to live with,” Mr. Martin said. “It’s better than television. There’s not a day I don’t look at or spend some amount of time with an artwork.”

Art makes an appearance in “Shopgirl,” his novella from 2000, and like “Shopgirl,” the new novel places a young woman, Lacey Yeager, at its center.

Two years ago he began writing “An Object of Beauty,” using books from his own collection — so large that he had to divide it between his homes in New York and Los Angeles — for reference. He particularly looked to his catalogs from Sotheby’s and Christie’s and at least three books on Maxfield Parrish, a 20th-century American painter who figures prominently in the novel.

The book is sprinkled with references to his experiences in New York. One character, a high-flying millionaire art collector named Patrice Claire, stays in the Carlyle Hotel whenever he is visiting from Paris. Mr. Martin used to keep an apartment there — a small one-bedroom, he said. Mr. Martin likes to ride his bicycle down the West Side bike path; so does Lacey Yeager, the fetching, ambitious art dealer from the book.

Real names are scattered throughout, largely to avoid having readers guess which fictional character is a stand-in for a real person.

Part of the reason to write about art, he said, was the challenge of capturing a world that is still a little foreign to him. This comes from a man who owned an Edward Hopper painting, “Hotel Window,” that he sold at Sotheby’s in 2006 for $26.8 million.

“The milieu of the book is the art world,” he said. “And the reason I chose the art world is I knew enough about it, but I don’t know everything about it. And I like that. I could have picked the milieu to be show business, but I feel like I know too much about that.”

Mr. Martin said he did not submit a manuscript to his publisher until it was complete, so that he would not be subject to deadlines or suggestions or any other kind of pressure.

He did receive a little pushback from Sotheby’s, which plays a small but slightly controversial role in the book, when one of the characters, a Sotheby’s employee, attempts a bidding scheme there. The people at the auction house were not pleased.

“They were a little nervous that a fraud takes place on the premises, but I convinced them that they come out to be heroes,” he said. (The fictional employee is promptly fired.)

He will soon find out how the art world feels about the book, which will be released Tuesday. Mr. Acquavella said he had just started to read it; Mr. Gagosian is giving him a book party.

The manuscript has been vetted by a couple of people who work for auction houses, and Mr. Martin made some small changes based on their suggestions.

He said he wasn’t concerned about whether the book is ever turned into a movie, as “Shopgirl” was. “My agent said, ‘We’ve got to send this out,’ and I said, ‘I frankly don’t care, because I’m not going to have anything to do with it,’ ” he said. “Although,” he added, “I’d be a good Barton Talley,” referring to one of the uptown art dealers in the novel.

“I gave it to my wife,” he said, finally breaking into a smile. “Her job is to say, ‘Fantastic!’ ”

Book review by JULIE BOSMAN from The New York Times, November 17, 2010.