Joan Linder is a Buffalo- and Brooklyn-based artist who is best known for her epic-scale quill-pen and ink drawings. Her works are at once highly representational of the real world yet slightly adrift, reflecting her own anxious perspective of the current direction of culture, politics and the products that create the fabricated urban landscape. She strives to capture the contemporary world as she sees it yet because she draws everything by hand in a relatively quick and loose manner, her drawings are filled with minor errors, random drips of ink, and elegant transpositions of line, resulting in quirky and human snapshots of life and the world that surrounds us. Through her personal scrutiny of her immediate surroundings, she seeks to examine the American experience.

Linder graduated with her Masters of Fine Arts from Columbia University in 1996 and she has been exhibiting consistently since. She has had solo shows throughout the United States and has been included in group exhibitions in many international cities including Tokyo, Berlin, Rio de Janeiro, Odense, and Copenhagen. Her works have been reviewed in many important art periodicals including The New York Times, Art on Paper, Art News and Art in America.

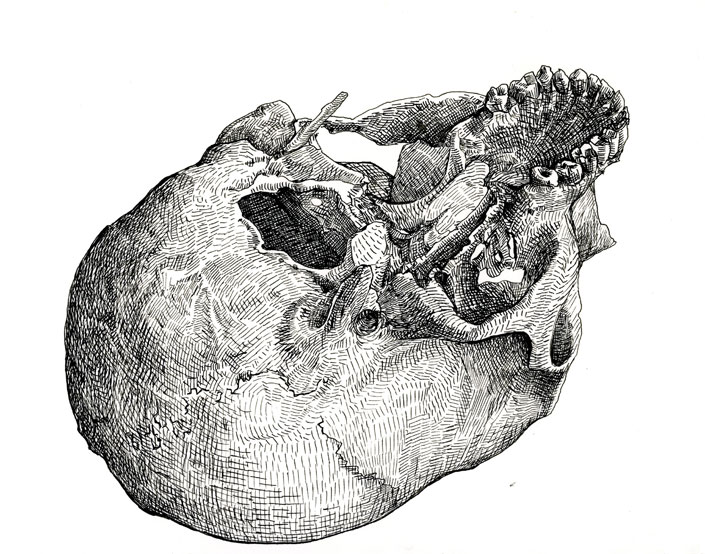

Since 2003, Linder has been represented by Mixed Greens Gallery in New York City and her massive-scale ink on paper drawing, Where Death Delights in Helping the Living (2010), is currently on display in that gallery’s group exhibition, “Functional Shift”. The following conversation, conducted via email during the summer of 2011 between Joan Linder and Heather Darcy Bhandari, offers an insight into this young artist’s thoughts on her own anxieties, her somewhat obsessive process, living in Buffalo, and drawing cadavers.

Heather Darcy Bhandari: Your work is often described as obsessive. Is that a fair description?

Joan Linder: Of course any description is fair. After all, isn't the perception of an artwork in eye of the beholder? Maybe you're asking if I’m obsessive? Well I do not feel particularly obsessive. I just feel like me. I don't think I ever washed my hands more than 20 times in a day.

It is true that I feel good when I draw, and years ago people would make comments like "you must be so calm," but actually I was working through a lot of frustration in the drawings. They were filled with anxiety about the state of the world (from listening to too much radio news and talk while I was working), or anxiety as I replayed and rewrote personal conversations.

Recently I am becoming calmer when I work, more meditative. I am using my time in the studio to find a kind of presence that is not distracted by electronic information and communication. Whenever possible, I work from life and practice perceptual drawing. I have always found great joy in the act of making and I have always had fidgety hands, so when I have pen in hand I have more focus; whether I am doodling in meetings or working on a large-scale piece. In terms of "making," the mark-making process that I have been engaged in is an additive process and one that allows me to see the progression of a drawing very directly, which gratifies some deep creative impulse. I am watching my drawing come to life, being built up from tiny marks like cells or atoms or bricks, generating an architecture of sorts.

HDB: I like that you talk about the process of building and describe all those tiny (obsessive!) marks coalescing into something larger. I often think of your bodies of work in a similar vein with seemingly unrelated drawings providing a collective context, narrative, or statement when shown together. I remember one exhibition in particular where you hung a 10-foot by 10-foot still life of your parents’ basement alongside the life-size drawing of a solider, rope drawings, a golf cart, and a moose. It was a beautiful show and the connections were powerful. In your last show at Mixed Greens, you included large-scale drawings of weeds, a tire, a cadaver, junk mail, your MFA diploma, and Louise Bourgeois' resume. Do you plot out the connections between objects before you make a body of work or is it a more organic process?

JL: I like that observation. I do make connections between my drawings and when I am putting a show together, the process is one of editing. In the case of an exhibition, I strive to bring together a group of powerful images that will resonate with each other without being didactic; where themes can be teased out and the viewer is allowed to make his or her own connections.

Most of my work comes from a personal place, so for me it is often operating on a number of levels. When I am drawing an iconic form, the object becomes an object of contemplation, and the longer I spend with each object, the more connections I make. When the drawings are hung in proximity they talk to each other.

Some of my ideas for drawings come from intuition, working in the studio and allowing myself that sense of play and freedom to draw whatever inspires me. Others come from carefully considering ideas or themes that I want to explore. As I make the drawings, I find my thoughts on my subject deepen. All my drawings are personal; each one is loaded with an experience that I had, and collectively they talk to me about trying to record a moment that will inevitably pass.

HDB: Your 2010 piece Where Death Delights in Helping the Living and the 2007 piece, The Pink, are extremely large-scale works that embody a complicated mix of everything you just spoke about. Can you explain the origin of those pieces and the importance/influence of Buffalo in your work? It's strikes me as important that two of your largest, most detailed, ambitious, jaw-dropping works are of locations in Buffalo. You could scout locations all over the world to represent your point-of-view, but you choose seemingly mundane locations right around the corner.

JL: For years now my practice has been premised on a personal scrutiny, through drawing, of my immediate surroundings which hopefully becomes an examination of a larger, contemporary, American experience: the transformation of the personal to the political. I react like a documentarian. For example, my struggles as a young artist attempting to fit into a day job at a major corporation led me to paint Xerox machines and create comic drawings about middle management. Since moving to Buffalo to teach at the University of Buffalo, I decided that I should be able to find subject matter here.

The first large-scale Buffalo drawing The Pink, came to me one night while out at the Allen Street Bar and Grill aka The Pink Flamingo. Frequented by a wide spectrum of Buffalonians including faculty and MFA students, it occurred to me while looking around that the bar is a still life, a space that represents over forty years of collective culture. It is a space that is at once public and, because of it's nature, feels deeply familiar and private. The Pink is an icon in Buffalo, offering a compelling amalgamation of objects and the detritus of blue-collar America: a sprawl of bottles, tchotchkes, political slogans, bumper stickers. It is the effluvia of American dreamers and reflects, in a microcosm, the ambivalence, chaos, and anger that sometimes define American culture. And so I decided to draw the whole thing—a panorama in ball-pint pen—where everything is drawn on a one-to-one scale and given equal importance.

One of the amazing opportunities that I have had as faculty at the University of Buffalo is the ability to work on interdisciplinary projects. My first trip to the Gross Anatomy lab at UB was to bring a class of figure drawing students in to draw the cadavers. I was instantly hooked and with the permissions of those that oversee the lab, I was allowed to audit the first year medical school’s gross anatomy class and work in situ and draw the cadavers, which I have done on and off for five years now. Having spent so much time in the lab, I became enthralled and fascinated with anatomy and also the culture of the lab itself.

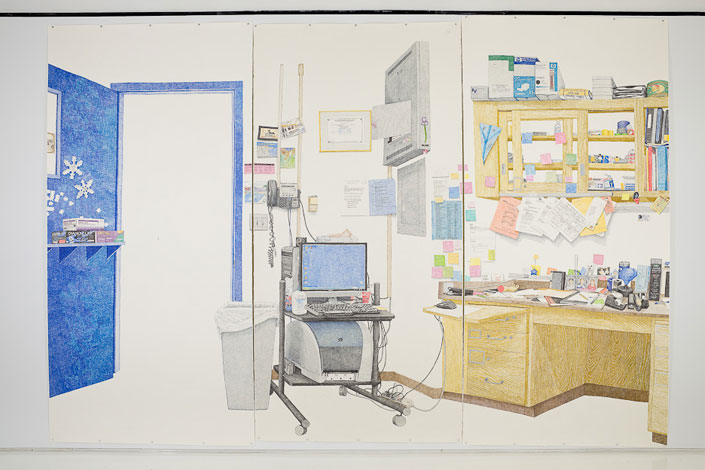

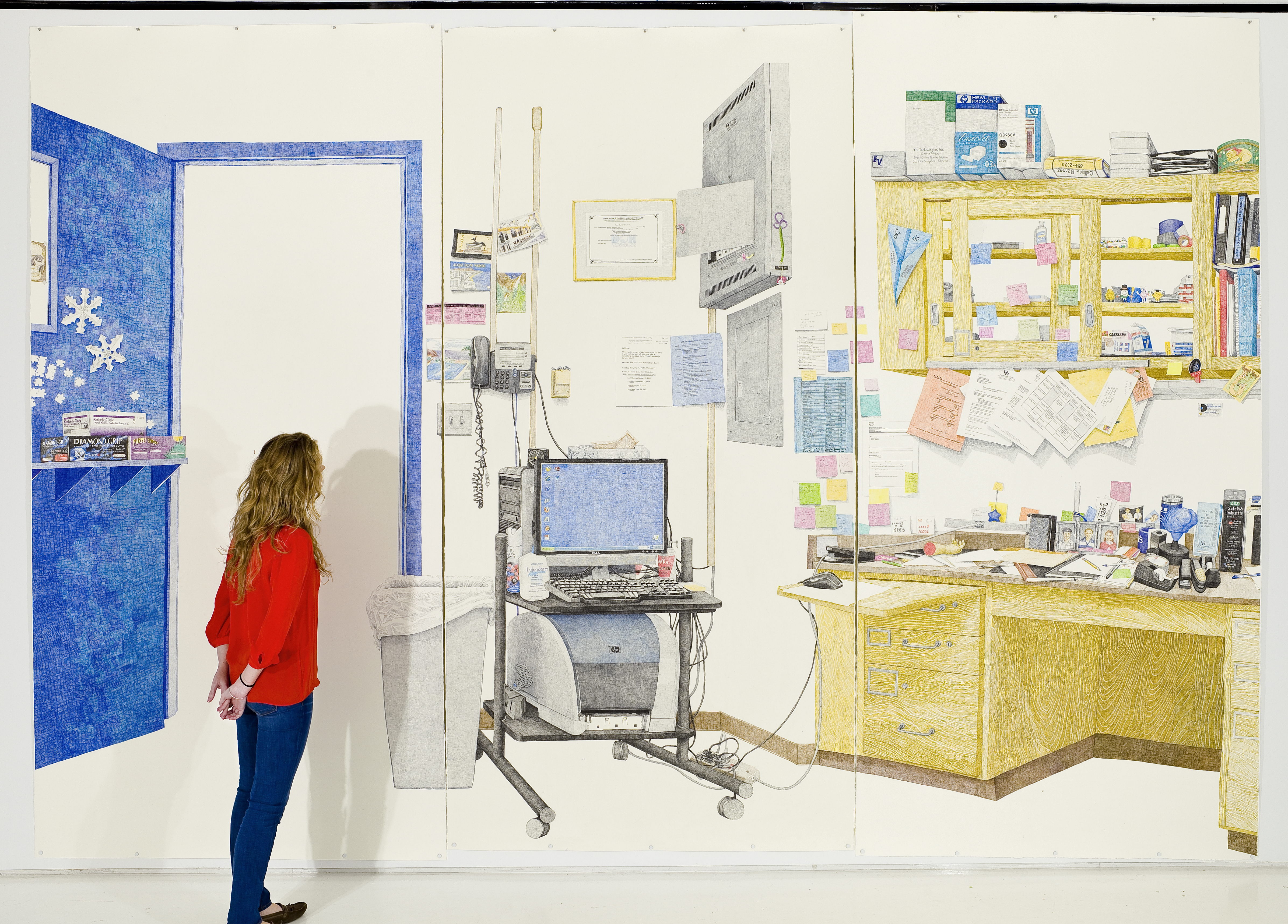

It was with this in mind that I embarked upon Where Death Delight's in Helping the Living, a 10 x 15 foot drawing of the interior office of those men who run the day-to-day operations of the lab. In the tradition of Rembrandt and Eakins, I wanted to make a heroically scaled piece that looked at the contemporary practice of anatomy. After years of thinking about how to go about framing my subject, I realized that I was interested in the metaphor that I found in Tom and Kevin's office. It is a place where the institution collides with the personal, as happens in office spaces, and even more magically the lab’s office, where death and life intermix in seemingly mundane ways within a framework of education and an incredible spirit of generosity.

In both pieces, the specific architecture and objects tell the story of how many lives (and deaths) intersect and for me became a compelling and poignant subject mater.

HDB: Now that you’ve addresses issues of life and death, I’d like to ask you some lighter questions. If you could go anywhere to draw, where would you go?

JL: The Canadian Rockies, Midtown in New York City, Walmart, and Niagara Falls

HDB: If you were no longer allowed to draw in pen, which medium would you use?

JL: Pencil

HDB: Which artists have had the most influence on your work?

JL: Goya and Updike.

HDB: What's your favorite drink at The Pink?

JL: A "Blue".

HBD: Your favorite body part?

JL: All of them - for different reasons.

HDB: Best place to draw in Buffalo?

JL: Niagara Falls, the old canal, faculty meetings…its hard to have a hierarchy of places to draw. If I'm drawing somewhere, it is usually a great place to be drawing.

HDB: Apple or PC?

JL: Apple

HDB: Heart or head?

JL: Head

HDB: Heels or flats?

JL: Heels of course

HDB: Ropes, whips, or both?

JL: Ha - your guess.

HDB: Sharks or robots?

JL: Sharks