An artist known for fantastically bloody paintings is getting in touch with his domestic side.

Barnaby Furnas works best when he allows a picture to get out of control. "One of the things I do well is let things be what they want to be," says the artist, referring to his new series of watercolors and the way in which the paint, on its own, conjures human features. "You wait to see a face emerge, and then you help that face along."

This love of spontaneity and experimentation informs much of his work, from chaotic scenes of the American Civil War to ecstatic portrayals of lovers embracing. In his modest-size studio in the Dumbo section of Brooklyn, Furnas, casually dressed and still boyish-looking at 37, talks easily about his creative process. He works alongside a rotating crew of assistants and his nine-year-old dog, a vizsla named Ester.

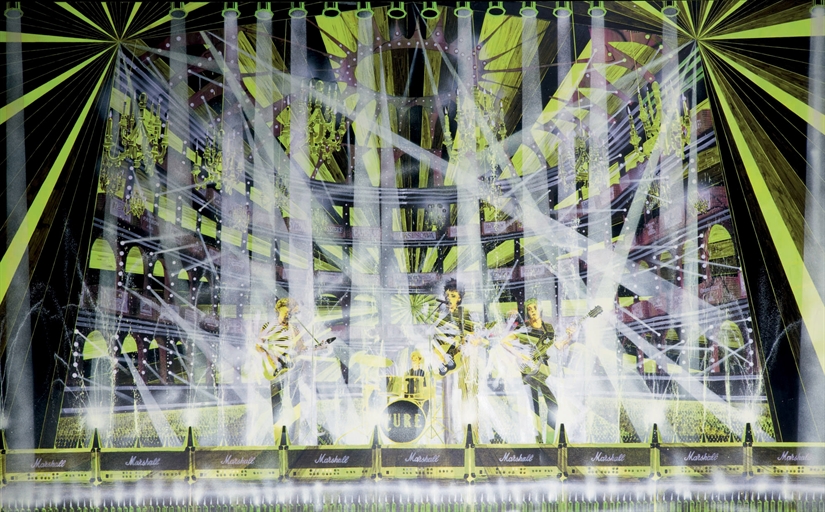

Hanging on or propped against the walls are examples of his eclectic output, past and present: a massive, kinetically charged abstract composition from his "Flood" series; in-process canvases, from another series, depicting the bands Spacemen 3 and the Fall performing in rock arenas; and some unfinished medium-scale portraits of what he characterizes as "Victorian people having this "Nude Descending a Staircase" moment," referring to Duchamp’s famous work from 1912. Those pictures, along with ones of women smoking, will be included in his show next month at Stuart Shave Modern Art gallery, in London.

Such relatively serene pieces are something of a surprise coming from a painter known for blood-spattered, violent subjects. He first landed on the art world’s radar with intense battle scenes like "Where the Boys Are (Iwo Jima)," 2000, and "Hamburger Hill," 2002, riots of motion and pigment, with mangled figures fighting under bright blue skies cut by gunfire. (Furnas cites movies like "Saving Private Ryan" and "The Matrix" as reference points.) These works, executed in either watercolor or urethane, are attention grabbing and overstuffed, possessed of what the artist calls a "retinal sizzle" that he credits to his days as a graffiti-spraying teenager in Philadelphia, where he was raised a Quaker in a house that he likens to a commune for social activists. Furnas says he fought for acceptance as an outsider in the racially mixed area, earning respect through his graffiti prowess. "It gives you something to offer," he says. "You’re not just some dumb white guy walking around — you’re participating, you’re doing something in the city where you do feel ‘other’ at times."

In addition to tagging walls, Furnas had formal training at an art high school, learning from a Caravaggio-obsessed teacher who had his students endlessly reproduce the Old Master. Furnas also visited New York with his friend Charlie White, now a photographer and filmmaker based in Los Angeles, touring galleries like Mary Boone and OK Harris with White’s father. "Once I found out there was an art world, I was determined to come here," he says.

The crop of graffiti artists operating on both the streets and in the gallery system also inspired Furnas, who remembers thinking, "Keith Haring — I could do that! Let’s go to New York!" He came to Manhattan along with White to study at the School of Visual Arts, graduating in 1995 and then spending several years assisting the painter Carroll Dunham, who became an influence. Furnas was simultaneously striving to develop his own style. He succeeded in a picture of a burning building, its inhabitants running to escape the flames: "It was the first painting I made where I invested myself in a story, a strong narrative — and also decided that things blowing up was a good way for me to go."

Dunham was teaching at Columbia at the time and suggested that Furnas enroll in the MFA program there, which he did in 1998. He recalls reading Columbia professor Arthur Danto’s "Beyond the Brillo Box," whose embrace of pluralism in artmaking gave him "a sort of permission" to do anything. He was also affected by the work of Kara Walker and began focusing on Civil War imagery, which he sometimes superimposes with references to later war scenes. "The confusion of fantasy with history seemed really rich," he says, "this idea of personal history being overlaid on top of actual history." Much as Walker resurrected cutout paper silhouettes, he explains, he revived the slightly out-of-fashion medium of watercolor. The technique was "traditional, even amateur," Furnas says. "I didn’t know how to use it — that was also attractive. Things I made looked awkward, and that was exciting."

Among the collectors and gallerists who regularly visited Columbia’s MFA open studios was the New York dealer Marianne Boesky, who had first seen the young painter’s work in a group show at Friedrich Petzel Gallery, in Chelsea. "I was blown away by the control he had over the [watercolor] medium," she says. "We began talking about working together and agreed that he should take time after graduate school to let his work evolve." In 2002 he had a well-received solo debut at Boesky, and has been working with her ever since; Furnas also shows with Anthony Meier Fine Arts, in San Francisco.

If history informs Furnas’s subject matter, his graffiti background is evident in his technique. "Graffiti is all about misusing, a guerrilla use of materials. Everything’s from the hardware store," he says, noting that 50 percent of what is in his studio now comes from the same source. And despite his focus on actual events and places, Furnas has never been concerned with verisimilitude. "The paintings are scenes in which everything is going at different speeds," he explains. "It’s cartoon people living in a cartoon world having really real, tight-focus photographic things happen to them." Most of these things involve death or dismemberment. In "Fountain," 2004, for instance, an unfortunate man gushes blood from stumps left by severed arms and legs. That image had an unlikely, innocent source: the Swann Memorial Fountain, in Philadelphia, designed by Alexander Stirling Calder, father of the modernist sculptor Alexander "Sandy" Calder. "It has all these animals spewing water," Furnas says. "It’s a permanent vomiting of water. That’s where I got the idea." Just as unnerving are later works, such as the "Bad Back" series, begun in 2004, of tortured human torsos painted on "canvases" of dried, stretched, and burned animal skins.

Furnas is surprisingly gentle and mild-mannered given his dark subject matter, or perhaps because of it, his work acting as a form of catharsis. "I think for many years the pictures were as loud and dynamic as I am quiet and reserved," he says. Furnas, his wife of 10 years, and their two young children live in what he calls "the cutest Dickens row house" in nearby Cobble Hill, a neighborhood not known for its outbreaks of havoc. Furnas spent last summer with his wife on Shelter Island, an even more idyllic place, to complete new work. The result is the watercolor series "Summer Smoker," suggested by the island’s middle-aged housewives whose husbands stay in Manhattan during the workweek. "They’re objects of lust for me," Furnas offers. "I’ve been married forever." Painting women is fairly new for the artist, and it’s clear that he feels some trepidation about it. He’s not quite sure who or what the female figures are: ghosts, or girlfriends, or goddesses. "Men making pictures of women is so fraught with baggage and projection," he says. "I’ve been okay with it being kind of harsh. These aren’t exactly flattering." The "Summer Smokers" are often eyeless, à la Modigliani, and some of them appear to be sporting gaping throat wounds. The contrails from the cigarettes are thin rainbows — a contrastingly uplifting motif that Furnas says is partly drawn from his studio assistants’ tattoos. Rainbows also appear in "Way to Heaven," his sexually charged series of watercolors showing fornicating couples. These were initially much more explicit. "We just had a baby," Furnas explains. "There’s not a lot of sex going on right now. You always make pictures of what’s not around."

In a similar vein, Furnas — a former smoker — has filled his most recent portraits with nicotine. (He admits a love for famous cigarettes in art, in particular Phillip Guston’s.) The subjects draw simultaneously on dozens of butts, each with a glowing tip rendered in the eye-grabbing "safety" orange that he is especially fond of. "These are pictures for my grown-up self," he says. "I think of them as bourgeois paintings." One depicts a lone man — perhaps a bachelor, perhaps a divorcé, Furnas hasn’t quite decided yet — his arm painted at multiple angles to capture the motion of his smoking. "The Twins" portrays a pair of cigarette aficionados modeled on an upper-class gay couple from Sharon, Connecticut, who are friends of the artist’s. All these works display delicate details painstakingly rendered: the wood grain of floors, the patterning of shirts and vests, the borders of pictures within the picture. "I’ve been looking at a lot of regional American painting," says Furnas. "I’d always been influenced by Charles Burchfield, Thomas Hart Benton. It feels like where my work should go — this American lineage."

Which is not to say that he’s lost his blood lust. Furnas gets excited talking about a projected new series rooted in a very American industry: whaling, captured in "Raft of the Medusa"-size action-packed canvases. He’s been brushing up on Herman Melville, watching whaling documentaries, and spending time at Marianne Boesky’s house on Nantucket. He’s planning to have some of these works ready in time for the London show, and some will be at Boesky’s booth at Art HK, in Hong Kong in May. "Dark — all that water. It encapsulates all the hubris and selfishness that has marked mankind’s time on the planet," Furnas muses. "I’ve got this image in my head: After they tire the whale out with the harpoons, to kill it they use hatchets to get into central arteries. They know they’ve hit it when the blowhole changes from water to blood. That’s perfect!"

By Scott Indrisek from the January 2011 issue of Art+Auction and ArtInfo.